Market capitalization, commonly referred to as market cap, is a fundamental metric in the investing world. It is used to evaluate the size and overall value of a publicly traded company. Whether you are a seasoned investor or just beginning your investment journey, understanding market capitalization can help you make better-informed decisions.

In this blog, we will explain what market capitalization is, how it’s calculated, its different classifications, and its role in investment strategies.

Market capitalization, often referred to as “market cap,” is a key financial metric used to determine the total value of a publicly traded company’s outstanding shares. It provides a snapshot of a company’s size and is widely used by investors to evaluate and compare companies within an industry or across sectors.

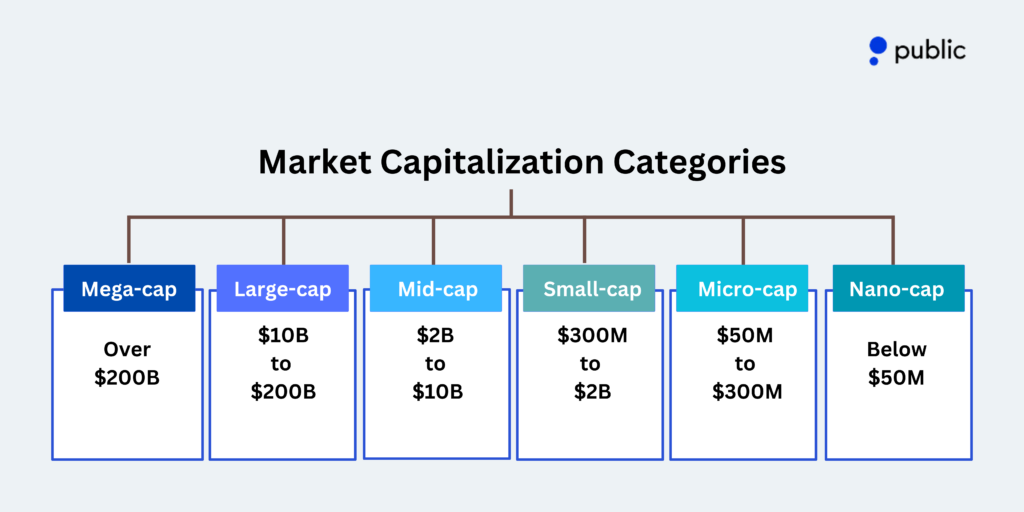

Market capitalization is often used to classify publicly traded companies into categories based on their total market value. These categories may help investors understand a company’s size, growth potential, and associated risk. Below are the common categories of market capitalization:

1. Mega-cap

These are the largest companies in the world, often recognized as global leaders in their industries. They are highly stable and may have established markets.

- Market cap: Over $200 billion

- Examples: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon

- Investor perspective: Typically considered low-risk investments with consistent returns but limited rapid growth potential.

2. Large-cap

Large-cap companies are established, financially stable businesses that dominate their industries. They are known for steady growth and reliable dividend payouts.

- Market Cap: $10 billion to $200 billion

- Examples: Coca-Cola, Walmart, Google (Alphabet)

- Investor perspective: Viewed as relatively safe investments with a balance of growth and stability, suitable for long-term strategies.

3. Mid-cap

Mid-cap companies are generally in the growth phase, expanding their market presence and revenues. They may strike a balance between risk and growth potential.

- Market cap: $2 billion to $10 billion

- Examples: Zoom Video Communications, Spotify

- Investor perspective: Offer higher growth potential than large-caps but may come with more risk due to smaller market shares or less established track records.

4. Small-cap

Small-cap companies are younger businesses or those in niche markets. While they have significant growth opportunities, they are more volatile and may carry higher risk.

- Market cap: $300 million to $2 billion

- Examples: Start-ups or regional companies

- Investor perspective: Often targeted by aggressive investors seeking high returns, but they may require careful analysis due to their higher susceptibility to market fluctuations.

5. Micro-cap

Micro-cap companies are small and speculative businesses, often in their early stages or highly specialized industries.

- Examples: Emerging technology firms or local enterprises

- Market cap: $50 million to $300 million

- Investor perspective: High-risk, high-reward investments suitable for investors with a high tolerance for volatility and uncertainty.

6. Nano-cap

These are the smallest and often riskiest publicly traded companies. Many may be new ventures or operate in unproven markets.

- Market cap: Below $50 million

- Examples: Penny stocks or very small start-ups

- Investor perspective: Typically avoided by conservative investors due to their speculative nature and lack of liquidity.

How to calculate market cap?

Market capitalization (market cap) is calculated using a simple formula that multiplies a company’s current stock price by its total number of outstanding shares. This metric helps determine the overall market value of a publicly traded company.

Formula:

Market Capitalization = Current Stock Price * Total Outstanding Shares.

Steps to calculate market cap

1. Find the current stock price:

Look up the current trading price of the company’s stock. This information can be found on financial websites, stock exchanges, or brokerage platforms.

2. Determine the total outstanding shares:

The total number of outstanding shares refers to the shares currently held by all shareholders, including institutional investors and company insiders. This information is available in the company’s financial statements or investor relations section.

3. Multiply stock price by outstanding shares:

Multiply the stock price by the total outstanding shares to arrive at the market cap.

Example of calculating market cap

Let’s walk through an example to see how market capitalization may be calculated for a company.

Scenario:

Imagine a company named XYZ with the following details:

- Current stock price: $25 per share

- Total outstanding shares: 40 million shares

Step-by-step calculation:

-

Identify the formula: Market cap = Stock Price * Outstanding Shares

-

Plug in the values: Market cap = 25 * 40,000,000

-

Perform the multiplication: Market cap = 1,000,000,000

Result:

The market capitalization of XYZ is $1 billion.

Based on this market cap, XYZ. may be classified as a mid-cap company, since its valuation falls within the $2 billion to $10 billion range. This classification can indicate that the company is in a growth phase and may offer moderate risk and potential for expansion.

The limitations of market cap

While market capitalization is a valuable metric, it has its limitations, and relying on it exclusively may lead to an incomplete understanding of a company’s potential or investment risks. Here’s why:

1. Growth potential in large-cap stocks:

A large-cap stock might seem too big to grow further, especially for investors looking for high-growth opportunities. However, even companies with market caps exceeding $10 billion may still have significant potential for expansion and profitability. This highlights the importance of not overlooking large-cap stocks solely based on size.

2. Returns per share may differ from market cap growth:

Strong returns per share can be achieved even if a company’s market cap grows slowly. For instance, share buybacks or efficient operations may enhance per-share performance, offering investors good returns despite modest changes in overall market capitalization.

3. Market cap does not guarantee growth:

A high market cap may create the illusion of stability or growth, but it doesn’t ensure a company’s success. For example, companies with large market caps might still face challenges such as declining revenue, outdated business models, or increased competition. This makes it crucial to look beyond market cap to evaluate a company’s overall fundamentals.

4. Limited insight into financial health:

Market cap reflects the market’s perception of a company’s value but does not provide direct information about its financial stability, debt levels, or profitability. A company with a high market cap may still struggle financially, making it vital to assess key financial ratios and other indicators.

5. Market sentiment can skew market cap:

Market capitalization is influenced by stock prices, which in turn are affected by market sentiment. This means that overvalued or undervalued stocks can distort the true picture of a company’s worth. Basing investment decisions solely on market cap may lead to missed opportunities or exposure to unnecessary risks.

Using market cap in investment strategies

Market cap can help guide investors in diversifying their portfolios. Here’s how it can guide your strategy:

1. Diversification:

Investors often balance their portfolios by including stocks from various market cap categories. For instance:

- Large-cap stocks: Provide stability and steady returns.

- Small-cap stocks: Offer higher growth potential but come with increased risk.

2. Risk management:

Large-cap stocks are ideal for risk-averse investors seeking steady returns, while small- and mid-cap stocks may appeal to those with a higher risk tolerance.

3. Growth potential:

Smaller companies often have room to grow, making small-cap stocks attractive for long-term investors.

Bottom line

With Public.com, you can access real-time market cap data, AI-powered analytics, and an intuitive platform designed for investors of all experience levels. Unlike traditional brokerages, Public.com provides access to multiple asset classes, including stocks, ETFs, crypto, bonds, treasuries, IRAs — all in one platform. Plus, with AI-driven fundamental data and custom analysis, you can explore market trends and gain deeper insights.

Sign up for Public.com today to explore market data, track assets, and stay informed with powerful tools at your fingertips.