In 1986, Nintendo released the highly-anticipated followup to 1985’s massive hit: Super Mario Bros., a direct sequel entitled Super Mario Bros. 2. An incremental design based on its predecessor, the game was incredibly difficult. Released on the Japanese Famicom Disk System, Japanese fans reveled in the challenge – and the game grew to become the most popular game on the system, ultimately selling nearly three million copies.

This story could stop there, except this game is completely different from the one that most NES fans on this side of the Pacific think of when they discuss Super Mario Bros. 2.

***

To understand how Japanese and American gamers ended up with two vastly different versions of Super Mario Bros. 2, we have to go back to 1985. At the time, Mario series creator Shigeru Miyamoto and his R&D4 team were hard at work developing The Legend of Zelda. Immersed in creating this gaming classic, they offloaded the development of the Super Mario Bros. sequel to the game’s Assistant Director, Takashi Tezuka.

Tezuka decided to develop Super Mario Bros. 2 by expanding on levels the original team had already developed. His vision for the sequel was to directly build off of the original game, offering audiences a challenge power-up rather than something entirely new. This is how we ended up with the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 – essentially a fun expansion of the original game.

As mentioned, Super Mario Bros. 2 was released and instantly became a hit in Japan. Once work on Zelda had wrapped up, Miyamoto’s team started developing a Mario prototype – what might have gone on to become Super Mario Bros. 3 had fate not thrown them a banana peel.

Miyamoto’s vision was to introduce vertical-scrolling into a game. He wanted to create a world where characters could move vertically by either climbing or stacking objects. Now, it is worth talking about Miyamoto’s approach to game design: he is known for working iteratively, having high standards, and always focusing on the “fun-factor” of a particular game mechanic and overall game play. Unless you’ve lived under a rock, you have probably played a game he has been involved with, and can personally attest to how well his process works at creating fun and immersive games.

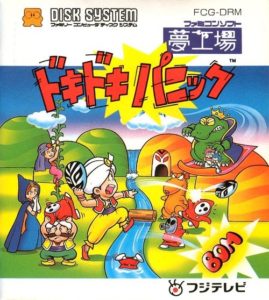

Following these standards, this Mario prototype was just not up to par. Miyamoto ditched the notion of vertical-scrolling and the team shifted their attention to a new project: a marketing opportunity with Fuji Television. Fuji approached Nintendo about producing a tie-in game for their “Communication Carnival Yume Kōjō ‘87” event, which was not only a technology exposition, but a futuristic global-themed bazaar meant to explore the possibilities of tomorrow.

To this end, the exposition had 3D movies, live performances with people dressed in futuristic outfits and masks, and a large area dedicated to playing video games. Fuji wanted Nintendo’s game to feature elements from Yume Kōjō. Specifically, they wanted to include the event mascots and capture the overall feel of the event in the game. These mascots were an “Arabian” family, seen zipping around a whimsical world on a magic carpet.

Knowing that they needed to find a way to incorporate these mascots, Miyamoto’s team returned to the Mario prototype. They expanded the game, finally finding a way to successfully integrate vertical- and horizontal-scrolling. The team also added in a few new elements, like throwing, lifting and carrying game mechanics.

This advergame, Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic, was released a week before the event started. Taking place in a storybook, the plot follows a family trying to defeat a monster who has taken over the world’s “dream machine” to create monstrosities. After falling into the book, which was given to the family by a monkey, they eventually defeat the monster by feeding him vegetables.

Around this same time, Nintendo of America was trying to find its footing in the American video game market. They needed a big hit to keep things going and worried that the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 was just too difficult to be a big success in the States. They needed a game changer, something different that would instantly grab people’s attention. Minoru Arakawa, then President of Nintendo of America, suggested they convert Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic back into a Mario game.

This request is not actually as strange as it sounds, as not only was the game a Mario prototype, but Nintendo had previously converted other prototypes into successful games (notably a scrapped Popeye into Donkey Kong and its successors). Shifting the storybook setting into that of a different dream world, Subcon, Mario and his friends awake from a collective bad dream in which they are called to liberate the inhabitants of Subcon from the evil frog, Wart.

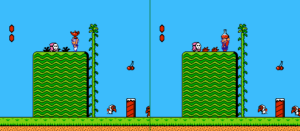

They reworked the original family (Imajin, Lina, Mama and Papa) into Mario, Princess Toadstool, Luigi and Toad, respectively. Despite not previously appearing in the Mario series, they kept the new game mechanics and expanded the world into 20 levels. This adapted game kept a lot of the odd whimsy of Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic, with its dancing cobras, now called Cobrats, and ostrich-riding masked enemies, Shy Guys, still wearing their Yume Kōjō masks.

This version of Super Mario Bros 2 was released in North American in 1988. With a distinctly different feel than its predecessors, this game brought an entirely new vibe to the Mario universe. Often considered the black sheep of the franchise, we might have never seen Mario explore new worlds without the influence of Yume Kōjō, or the Mario universe include so many cutesy anthropomorphic things, like Bob-Ombs, Hoopsters, Pokies and Fry Guys.

Far from tanking Nintendo’s standing in the American video game market, Super Mario Bros. 2 was critically well-received. It went on to become the Nintendo Entertainment System’s (NES) fourth-highest selling title, and was eventually released in Japan on the Famicom in 1992 as Super Mario Bros. USA.

Beyond its interesting development history, Super Mario Bros. 2 also introduced several lasting elements into the Mario series. Beyond the aforementioned vertical-scrolling, this game was the first time that Mario and Luigi were different heights, an artifact of Luigi’s “Mama” Yume Kōjō character being taller than Mario’s “Imajin.”

While it remains the only Mario game in which you cannot defeat enemies by jumping on them, it was the first to introduce the lifting and throwing of enemies, a game mechanic that has appeared in several subsequent games. Super Mario Bros. 2 also introduced several characters that still appear in the Mario universe, and served as the first outing where Princess Toadstool and Toad were playable characters (just try to imagine Mario Kart 64 without Toad).

In 1993, the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 (the difficult game), was finally released internationally. You might recognize it as Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels, so named as a nod to the game’s development history and how closely gameplay hewed to the original. Slightly reworked versions of both games would appear in the Super Nintendo Entertainment System’s (Super NES) Super Mario All-Stars Collection, which was also released in 1993, and the 2001 Super Mario Advance release for Game Boy Advance.

With perhaps one of the most circuitous and famous development histories of any video game, Super Mario Bros. 2 is a gaming legend in more ways than one. It is hard to imagine the Mario franchise without many of the elements introduced by these odd turns of events, or what the franchise would have grown to become without these influences. In the end, Super Mario Bros. 2’s development is a tale about innovation flourishing in the face of adversity.

Let’s just hope we never wake up to discover it was all a dream.