I was six. Almost seven.

Reebok didn’t make them in kids’ sizes yet so I couldn’t even get them, but one of the first products I can remember wanting was a pair of Reebok Pump sneakers.

The Reebok Pumps were a pop culture phenomenon even before they went on sale in November of 1989. They were famously and controversially expensive—$170 at launch, an outlandish figure that led to a moral panic in the nation’s newspapers. Reebok, until then previously best known for women’s aerobic footwear, even managed to briefly pull ahead of Nike in market share as a result. They are etched in basketball lore: Legendary dunker Dominique Wilkins—the future NBA Hall of Famer nicknamed “The Human Highlight Reel”—wore the Pump for his 1990 Slam Dunk Contest win. The next year, Dee Brown, a 6-foot-1 rookie, beat all-time dunker Shawn Kemp in part by incorporating the Pump into his dunk routines. They had a controversial “banned” commercial. They inspired legions of knock-offs. They even ended up in political cartoons, which tend to only add new tropes about every half-century.

I asked my mom about it recently.

“When you wanted something,” she said, “it was like a quest for you.” But I never got them. I ended up with a pair of L.A. Gear Regulator sneakers, a $65 knock-off.

I’ve never owned a pair of original Pumps. They are no longer a big hit. Pumps were a blip in the history of sneakers—an early 1990s fad. By the time POGs hit, Pumps were on the way out. Today a successor to the original shoe is the only Pump sneaker the company sells. How’d this happen?

In the 1980s, sneaker companies were all about pioneering new gimmicks.

Reebok gained market share in the mid-80s by connecting its sneakers with the aerobics craze, but Nike commandeered the space by the late 80s with its Air Jordan line and its Air Max running sneakers with visible air.

Reebok president Paul Fireman wanted new tech to counter Nike, and put engineer Paul Litchfield in charge of a project to build a customizable sneaker. Litchfield and his team, working with the consultancy Design Continuum, came up with the Pump: a sneaker with a big button on the tongue that allowed the wearer to “pump up” the sneaker each time they put it on.

Unveiled to the world at a trade show in March 1989, the sneaker was introduced to the public and pushed as the latest in athletic tech in September of that year. One spokeswoman hinted to the Associated Press about the benefits to athletes: “It creates a totally adjustable kind of shoe with support around the ankle.” Another basically said no other sneaker truly could fit as well as the Pump: “Traditionally basketball players have oddly shaped feet. Years of athletic training, broken bones and the fact that they are so tall all make finding a well-fitting shoe very difficult.”

The Pump wasn’t the only inflatable sneaker to hit the market in late 1989.

Nike actually beat Reebok to the market with its Air Pressure—five dollars more expensive, but inflated with a separate air pump that the wearer attached to the back of the shoe. Nike was specific that this wasn’t a mass-market sneaker. “It’s specifically for basketball players with unusual ankle problems,” a spokeswoman said.

Reebok, however, did aim at the mass market. An ad campaign with Dominique Wilkins talked up the athletic benefits, but also took aim at Jordan. “So Michael,” Wilkins said in one, “if you want to fly first class, Pump up—and Air out.” Another commercial that aired in early 1990 showed two bungee jumpers: One wore Nikes, the other had on Reebok Pumps. The man in Nikes slipped out of his sneakers, falling to his implied death.

The ad was banned. It inspired sales anyway. “I first got ’em because they were controversial,” a 20-year-old told a newspaper in 1990, referencing the commercial. “And people said ‘It must be nice to spend 200 bucks on sneakers.’”

The sneakers garnered even more fame for being expensive. They quickly became a status symbol, sparking what can best be described as a moral panic. “SNEAKERS LEAD TO CRIME,” read the headline to one newspaper letter to the editor. The letter, from a counselor at a school, was typical of much early-1990s drugs and crime commentary: “When asked why they ever got involved with selling drugs, the answer is often, ‘Because I saw my friend with a pair of pumps, so I had to get a pair. Mom couldn’t afford them, so I did what I had to do.'”

All of this simply made the sneakers even hipper. “Not only were the shoes exciting, and dope, and they were on the right people, but they were in their ads attacking another brand,” says sneaker branding historian Sean Williams. “That’s gone these days—no brand attacks another brand. And Reebok was willing to do that.”

It also helped that the sneakers were just fun to wear. Russ Bengtson, the longtime sneaker culture writer and former SLAM editor-in-chief, was in his late teens when they came out. He wasn’t paying $170 for a pair of kicks, but he tried them on. “I don’t know exactly how the technology would help you per se, but you could definitely feel it,” he told Otis. “I definitely remember trying the shoe on and pumping it up and it’s like, ‘Whoa, it’s tightening around your foot.’ Like, ‘This is cool.’”

Employees at Reebok reaped the benefits. Longtime sneaker designer Steven Smith, now on the Yeezy sneaker team, moved to Reebok just when the Pump was about to launch. He’d been playing roller hockey with Litchfield, the engineer; the two were able to use the sneakers as currency. “We were at the big [trade] show, and went over to the Rollerblade guys and they were like, ‘Aw, you guys work for Reebok? Can you get my kid a pair of Pumps?’ So we got their kid a pair of Pumps and they sent us a case of Rollerblades! Holy crap. Those were worth five times what the Pump shoes were, but bring it on.”

A 1990 Boston Globe article estimated Reebok sold $200 million in Pumps that year—to less than $10 million for Nike’s inflatable sneaker. That year, Reebok released several new models of the Pump, all of them cheaper than the original model. They eventually came in tennis models, endorsed by Michael Chang, and golf shoes, endorsed by Greg Norman. The Shaq Attaq 1, worn by hyped rookie Shaquille O’Neal, featured Pump technology. Eventually, Reebok sold more than a billion dollars worth of Pumps.

The market got saturated with Reebok’s models—and with clones. This wonderful history of inflatable sneakers lists nine Pump knockoffs, from the L.A. Gear Regulator that I got to the Jox Pulsator to the Franklin Intimidator. (There was also the Spalding Typhoon, proving that not every Pump knockoff ended in –or). Reebok sued L.A. Gear, eventually winning a $1 million licensing settlement.

And yet, by about 1994, the novelty wore off. People eventually were just content to tie their sneakers. DJ Senator, a Pump collector with 500 pairs, told ESPN for a story last year that Reebok oversaturated the market. “It just got flooded and then once they’re sitting, nobody wants them,” he said. “It’s not cool anymore, and nobody buys them.” Reebok occasionally retros an old Pump sneaker, but they’ve never been a hot resale item.

Except for one.

Steven Smith came to Reebok after stints at Adidas and New Balance—where he designed the iconic 574. He was hired to be part of a new creative team at Reebok, Advanced Concepts, in 1989, but before that team came together, he bounced around departments in the company. Naturally, he was intrigued by the Pump.

He began experimenting with it. He started taking parts off the existing sneaker. On his own, he drew some sketches of what would eventually become the Instapump Fury, the Pump sneaker that Reebok still produces today. Smith says people would see his sketches and say: “What is wrong with this guy? What is with this crazy-ass shoe?”

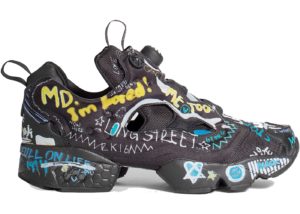

Released in 1994, the Instapump Fury is a wild-looking sneaker. It doesn’t have laces. It doesn’t have a tongue. It pumps around the foot to fit. It looked like nothing else on the market then—or now, even. The minimalist sneaker is attuned to Smith’s Bauhaus design philosophy: While other Reebok sneakers at the time used about a hundred pieces, the original Instapump Fury used about 20. The Pump was a gimmicky sneaker. The Instapump Fury is all function.

Maybe that’s why the Instapump Fury is the sneaker that has stuck around. Reebok currently sells Instapump Fury sneakers for that same $170 price tag of the original Pump. (There’s one with Boost technology from Adidas, which bought Reebok for $3.8 billion in 2005, that sells for $200.) The sneaker has also become a high-fashion icon. The hip Vetements label frequently collaborates with Reebok on new Instapumps, including an incredibly-cool $760 “Black Scribble” model. Opening Ceremony recently did an Instapump collab. The base that Steven Smith created has become a canvas for other designers to use.

For Smith, that feels pretty great. “For me as the designer of it—I was a younger guy—It’s pretty epic, you know?” he says. “I believed it was the right thing to do. And I fought with a lot of upper management there to get it out—because I knew it was right…They fought it tooth and nail because it was disruptive. It was different. It made them uncomfortable. A real design breakthrough should make you uncomfortable… looking back on it, 30 years later, it’s like, ‘I did the right thing.’”

So maybe it doesn’t matter that I never got a pair of original Reebok Pumps. Maybe what I should really be going for is that perfect pair of Instapump Furys—the Pump sneaker that actually managed to last.