The United States of America briefly lost its collective mind over stuffed animals 25 years ago.

Beanie Babies — the slumpy, pellet-stuffed animals that retailed for $5 — became a hot collector item with skyrocketing prices and an outsized belief that the right stuffed bear might one day fund your kids’ college education.

A little over two decades ago, the world went wild for Splash the Whale and his stuffed buddies. Police traded Beanie Babies for guns in Illinois. A Nevada couple had a custody battle over their shared collection when they got divorced. People were smuggling Beanie Babies into the United States from Canada.

Today, there’s a Beanie Babies documentary in the works that will inevitably arrive on Netflix. So, how did a collection of inexpensive cuddly buddies end up selling for thousands of dollars in the late 1990’s?

Let’s look back at what drove the Beanie Babies craze, what the market is today for the plush animals, and what the rise and fall of the stuffed animal resale market can tell us about collectibles now and in the future.

The Beginning of the Beanie Babies Boom

H. Ty Warner, the founder of the toy company Ty Inc., wanted to create an affordable, adorable stuffed animal. Instead, he unleashed a cultural phenomenon and investment bubble.

Beanie Babies arrived on the scene at the Toy Fair in New York City in 1993. They had cute names — Legs the Frog and Flash the Dolphin — and bodies that could be posed because of the plastic pellets (beanies) inside. The toys proved popular because they were different. But it wasn’t until Warner hit on a clever marketing strategy that Beanie Babies went from closet shelves to bank vaults.

In 1995, Ty began “retiring” animals. The decision to stop producing a toy that was still selling is a classic example of artificial scarcity (you know FOMO, right?). That tactic combined with Ty’s unique distribution model — they only sold 36 of any one animal to independent retailers at a time — created a market frenzy.

While the Beanie Baby Bubble is often characterized as a singular moment of irrational investing, the explanation is a bit more complex. Long before the recent Pokemon frenzy, new Beanie Babies arriving in stores were an event. Adults flocked to their local shop to try and snag a Pinchers the Lobster before it sold out.

Those early collectors created a cottage industry offline. There were pricing guides and magazines that touted future values, and plastic protectors designed to keep the tags attached to each stuffed animal in mint condition. But collectors still needed to reach a larger pool of buyers.

The resale market for Beanie Babies exploded thanks to a new web upstart: eBay. The fledgling online auction company launched in 1995 and within two years, Beanie Babies would account for six percent of all sales on the platform. The height of the mania may have been in 1997 when McDonald’s included Teenie Beanie Babies (miniature stuffies) in Happy Meals. Even kids thought adults had gone crazy by then. By 1998, Ty Inc. had more than $1 billion in annual sales.

The end of the craze came at the turn of the millennium when Warner made a surprise announcement. His company would stop making Beanie Babies at the end of the year. Beanie Babies were no longer the cool new toy as Pokémon and the Furby topped wishlists that year. Although Warner later agreed to keep making the stuffed animals after a predictable public outcry, the bubble had been pierced.

The market for Beanie Babies crashed alongside the dot-com bubble in 2000. As resale prices fell, collectors cracked open their Rubbermaid containers, and the market was flooded with an avalanche of inventory. The balloon of artificial scarcity was punctured. The resale market nosedived.

What’s the Market for Beanie Babies Today?

While a number of beanie babies sell for less than their original sale price of $5, there are still valuable versions of the plush toys. The stuffed animals that sell for higher prices are typically rarer — an early edition, a misprint or name change along with a limited run size — that makes a given animal harder to find. Those rare Beanie Babies like Peanut the Elephant (in Royal Blue) might sell for hundreds or, on occasion, a few thousand dollars.

Although it’s tempting to see five or even six figure listings on eBay, collectors shouldn’t expect a massive windfall from the bears in their attic. Motherboard dug into high dollar listings earlier this year and couldn’t prove that the sales were legitimate. Leon Schlossberg, an avid Beanie Babies collector and historian, was more blunt. “Those are bogus,” he told Motherboard.

What Can Beanie Babies Tell us About the Future of Collectibles?

When Beanie Babies exploded in popularity, the market was imperfect. The original boom was driven by speculation and a belief that prices would continue to skyrocket.

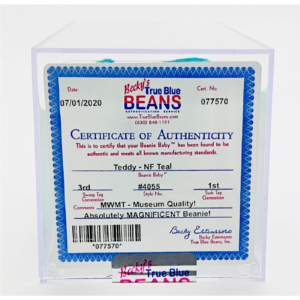

Today, the collectible Beanie Babies market is more transparent and logical. Over the past two decades, the community has come together online. A trio of longstanding collectors — Becky Estenssoro, Karen Holmes, and Karen Boeker — have developed an updated pricing guide, while Estenssrro runs True Blue Beans, an authentication service that works like card or video game grading.

New fads will always have pricing imperfections and speculation but established collectible markets are more predictable because of data about the condition of items and hard numbers attached to sales.

Beanie Babies made Warner one of the 900 richest humans on the planet and are still relevant, in large part, because Ty Inc., never stopped making them. Ty also added product lines — Beanie Boos and Teeny Tys — that trade on the nostalgia of a cuddly bear rediscovered on a closet shelf.

The reason Beanie Babies haven’t experienced a resurgence like Pokémon, baseball cards, or comic books, is because they’ve never really changed. While a documentary is in the works, Beanie Babies haven’t driven our cultural conversation in two decades. Pokémon developed a host of shows and games that bridge the gap between generations. Pokémon GO brought Charizard into our world with virtual reality. Baseball cards date back more than 100 years and physical sports cards have recently evolved into digital collectibles. Meanwhile, comics are providing a host of storylines for blockbusters at multiple major movie studios.

But nostalgia is still a commodity and the kids of the 1990’s have turned into adults with disposable income. The value of Beanie Babies, in many cases, might be determined by emotional connections, as much as financial considerations. Nostalgia has fueled the market for classic video games, comics, and Pokémon — the trading card game that helped usher out the era of Beanie Babies.

And artificial scarcity combined with a cuddly buddy still works. Consider the current Squishmallow craze among the TikTok set.

“I think these are so popular because of their collectability factor,” Jackie Cucco, a senior editor at Toy Insider, told The New York Post earlier this year. “People go crazy hunting them down.”